The excitement over AI in recent months has drowned out some significant news in the cybersecurity world. LastPass, a popular password manager, has been in the spotlight recently for a series of dramatic cybersecurity breaches in 2022.

While I applaud them for their candor and transparency in sharing the issues and their response, at a fundamental level, their approach thus far is a Masterclass in cybersecurity theater--lots of activity without truly solving the underlying problem.

LastPass customers should consider other alternatives like OnePassword or Apple's iCloud Keychain. More importantly, techniques like zero trust, cyber-resilient design, and avoiding security theater can help other companies avoid LastPass' mistakes.

Background

For those who may not know, a password manager is a tool that helps users store and manage their passwords for various online accounts like banking websites, e-commerce sites, and the like. The password manager can generate strong, unique passwords for each account and auto-fill login forms, making it easier for users to maintain good password hygiene. Instead of having to remember multiple complex passwords, users only need to remember a single master password, which grants access to their password vault. More sophisticated password managers allow companies to create groups so that passwords and security keys can be shared and managed amongst teams.

Bottom line: password managers are beneficial and valuable tools. For almost all ordinary cases, they are a much better solution than keeping post-its of passwords stuck to your computer monitor!

Needless to say, a service that stores hundreds of millions of active usernames and passwords for access to banking accounts and other sensitive sites is an incredibly juicy target for hackers. Any company in that business needs to have extreme cybersecurity expertise.

LastPass has failed this test so far.

What Happened?

In 2022, LastPass suffered at least two security breaches. In the first breach, the attacker compromised a software developer and gained access to the source code and other internal secrets of the LastPass system. In a subsequent attack, another engineer was compromised, and the hacker was able to gain access to LastPass customer data. The write-up from the LastPass team is worth reading, particularly for readers with a technical background. (https://blog.lastpass.com/2023/03/security-incident-update-recommended-actions/)

By themselves, these attacks were very damaging. The more significant issue is: "what else do we not know about yet?".

In Sun Tzu's renowned treatise "The Art of War," he said:

"All warfare is based on deception."

This principle highlights the importance of concealing one's true intentions and capabilities while exploiting the enemy's vulnerabilities. This idea has been with us for thousands of years, in real warfare, in cold wars, in politics, and of course, in cyberattacks.

One common technique in the arsenal of deception tactics is the idea of "one to find, one to keep.". You'll see this often in movies and TV shows, such as when the hero protagonist pulls out a secret knife or other gadgets while locked in a cell:

In cyberattacks, this same idea is frequently employed. Attackers going after a high-value target like LastPass know that the company has security tools and teams watching the systems 24x7. These teams are expecting an attack.

So give it to them. Launch a distributed denial of service attack (DDOS) to occupy the security teams while the real hack happens elsewhere.

In the case of LastPass, by LastPass's admission, the hackers had access to and control of computers used by their engineers. Engineers in a software company are typically (and almost of out necessity) all-powerful. They have to be--they are building the product! Now the attackers have that power.

So what did hackers do with that power?

There is no way to know for sure. There are countless things an attacker could do, like placing a backdoor in the system, allowing them to return when they like to wreak more havoc.

(only modern backdoors are way more sophisticated and harder to detect!)

This puts LastPass in a tough dilemma. How can they prove they are safe now?

Imagine a restaurant where someone poisoned the food with an indetectable poison. What would you do? How would you possibly recover from that?

Well, you would toss all the food, of course, and anything else that might possibly be poisoned, and you'd start over from scratch. You would need to do more than just visually inspecting the food to see if there was poison.

There is a historical precedent for this "rebuild it all" mentality.

In the 1970s, during the height of the Cold War, the US Embassy in Moscow faced a severe security breach. The building, constructed by Soviet crews, was found to be riddled with listening devices embedded within the walls placed there during construction. The situation was so severe that the embassy was deemed unusable for sensitive discussions. The US State Department had no choice but to tear it down and completely rebuild it (at enormous expense!)

https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/U-S-Finally-Opens-Moscow-Embassy-Building-was-2714015.php

For LastPass, a complete rebuild (literally tossing all their computers and getting new ones) would likely be expensive and time-consuming, so, unsurprisingly, LastPass has not taken this step. But I suspect it would have been cheaper than what they are going through now, particularly factoring in the employee time needed to deal with the breaches.

Unfortunately, this type of short-term thinking happens frequently. I once did a cybersecurity audit for an insurance company. They did not like that I pointed out a large number of vulnerabilities, so they commissioned another study to say they were fine. Sure enough, they were hacked. A similar thing happened at a major infrastructure company: very obvious weakness in their systems, and sure enough, they were hacked as well.

After the fact, I-told-you-so remarks are not helpful, though. Proactively addressing cybersecurity issues has identifiable costs. Dealing with a hack sometime in the future is unknown. How do you plan and prioritize against these uncertainties and against certain budget realities?

Lessons Learned

Fortunately, with some forethought and planning, building a robust and secure environment in nearly any company is possible without incurring extraordinary expense.

A complete security plan is obviously outside the scope of this post, but here are three things to consider more deeply:

Zero Trust

Zero trust is a somewhat abused marketing term, but conceptually it's simple. Assume the least amount of trust possible with any digital system or digital interaction. In many legacy environments, there is a concept of a corporate network and corporate firewall. Once a user or computer is past the firewall, it can access anything. That's convenient for users and even more convenient for attackers!

On the other hand, zero trust networking solutions require authentication and authorization for every user for every service. There is no 'blanket trust' provided. This doesn't sound very easy, but it is analogous to how services on the web work today--as a website, you can't assume the visitor to your site is trustworthy; they have to authenticate first for anything sensitive. There are a number of companies like ZScaler that provide relatively easy-to-use Zero Trust solutions.

Cyber-resilient design

Cyber resiliency is not so much a product as it is a way of thinking. Think through every aspect of your organization, be it people, processes, or technology, and ask the question: "what happens if this piece is compromised?". Then devise an approach to mitigate the risk.

As a simple example, for your bank accounts, make sure wire transfers, or at least wire transfers above a certain threshold, require at least two people to sign off. Similarly, many of us learned the hard way last week of needing a backup bank, for that matter!

One of the most challenging aspects of resilient design is knowing where to draw the line. Every organization will have to draw the line somewhere; everybody has finite time and resources! For example, do you need to have a backup email system in case your primary one fails or is compromised? I've taken this step at my company, but at a larger company, it could be untenable. Do you need to have multiple cloud storage providers? I do this as well, but again, in other situations, that might not be a practical approach.

Wherever you draw the line, do it as deliberately as possible and think through the tradeoffs.

Security theater

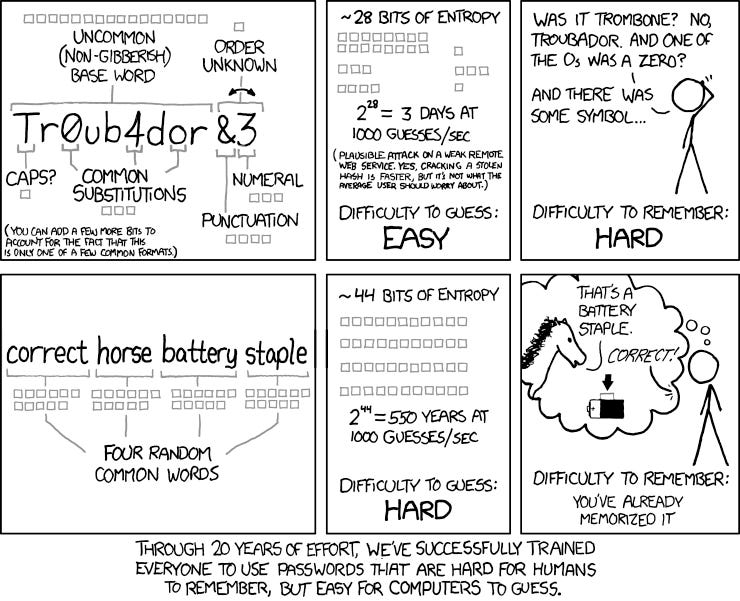

Speaking of tradeoffs, one of the easiest places to consider tradeoffs is in security tools and processes. Consider for a moment your organization's password policy. I still see to this day password policies that make no sense: 8-character passwords with punctuation and the like. Short passwords are easy for hackers to break and difficult for users to remember (so the real password strength is whatever the password reset policy is). This cartoon from XKCD illustrates the concept wonderfully: https://xkcd.com/936/

It would be much better to invest in a good multi-factor authentication system like Auth0.com than spend time and money on an ineffective password policy.

One of the most intriguing details of the LastPass hack was how the attackers completely bypassed the EDR (endpoint detection and response) tools they had in place without being detected. This is par for the course for hackers; there are dark web services that let them practice avoiding many common security tools. While tools like Microsoft Defender will keep out the casual hacker (much like a locked door would keep out a drunk, would-be amateur thief), the competent hacker will easily bypass them.

In the cybersecurity industry, at least at the high end, there is a concept called "security theater." Security theater is when an organization spends more time on pretty reports and running checklists than actually thinking through and building a secure and resilient organization.

This phenomenon afflicts even large, well-established tech companies that should know better. I was involved in a three-month-long security audit with one such firm, and as part of that process, their checklist required them to run EDR scans for two months on a set of old laptop computers. Not only would that process have yielded unreliable data (as LastPass learned), the computers in question were already scheduled for decommissioning and recycling. It was security theater at its finest.

Thus the key questions for your organization: from a cybersecurity perspective, what are you spending money on (and more importantly, people's time on)? Which of those products and activities is actually providing real security value against a competent attacker? Focus on those, and cut the rest. Use the savings to shore up any gaps in building out a more cyber-resilient organization.

To close on the LastPass hack, that's what is missing from their response. All of their published actions in response to the hacks are reasonable. However, they do not seem to have done anything to address the fundamental cyber resiliency of the company. Until they do, I am confident they will be hacked again.

Keep your own company from becoming the next LastPass! If you need any pointers or help, please get in touch with me privately, and I will connect you with some great resources.